How to rescue a homemade cocktail: ‘Don’t worry about having a bottle of each liquor’ | australian food and drink

The alchemy in preparing a cocktail is making it more than the sum of its parts. No one flavor or sensation should dominate. If, taking a sip, you find yourself thinking “too strong”, “too sweet”, “too sour”, “too bitter”, then your drink is out of balance. Don’t worry! It can be saved.

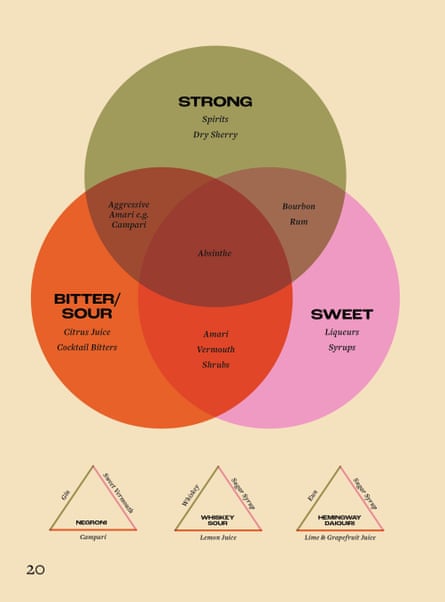

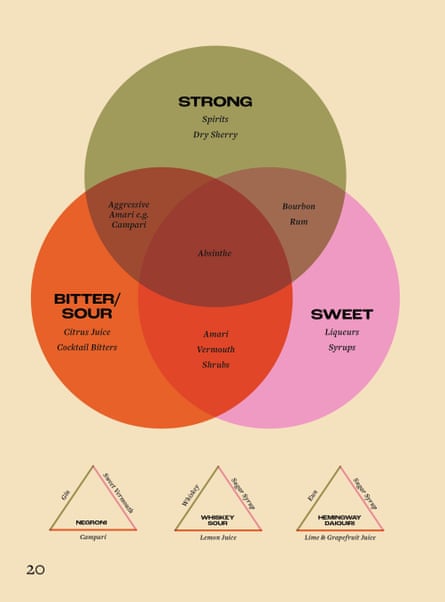

The three sides of the triangle of taste

The foundations of every successful cocktail—strong, sweet, and bitter (or sour)—form the three sides of the triangular base that has underpinned cocktail creativity from 1806 to the present day. I call this the “triangle of taste”.

You are watching: How to rescue a homemade cocktail: ‘Don’t worry about having a bottle of each liquor’ | australian food and drink

Strong: The “strong” element is the engine of your cocktail. It is the base, what gives it body and backbone. The strong part of the cocktail usually has to be dry (no added sugar), and it usually brings a drying effect to the whole drink, either through a flavor, a spice or a minerality.

Sweet: “Sweet” is often seen as a dirty word because people have suffered too much. sticky and sick cocktails. But sweetness is an integral part of any cocktail as a counterpoint to sour and bitter flavors and to add body, texture and depth. If you don’t believe me, try a mojito without the sugar syrup (a pretty common request, sadly). Rum, lime and mint sweep across the palate and the already light flavor quickly dilutes as the ice melts, until you’re drinking sour mint water with a hint of ethanol. It’s an experience I do my best to discourage customers from.

Used wisely, sugar is the salt of the cocktail world: it enhances desirable flavors while smoothing out any harshness, without being a perceptible flavor itself.

Disassembling the three ‘flavors’ of cocktails: strong, sweet and bitter/sour.

Disassembling the three ‘flavors’ of cocktails: strong, sweet and bitter/sour.

Bitter or sour: The interplay between these elements and the sweetness is what keeps you coming back for more.

Of course, sour and bitter are two very different tastes. “Sour” flavors – acid – tingle on the palate while bitter flavors hit you in the back of your palate and linger, giving your drinks plenty of length and spice. They typically come from woody botanicals like amari or cocktail bitters, and often produce the kind of drink to meditate on in a leather armchair: the Manhattan, for example.

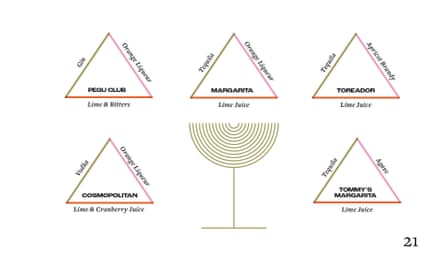

Test the triangle of taste

Ran out of rye but have some rum hanging around? No problem. The orange liqueur bottle is empty but you have apricot brandy? Sweet like. Most cocktails have variations that simply swap one ingredient for another on the same side of the triangle.

Let’s use the daisy as an example:

Margarita (tequila, lime, orange liqueur)

Change sweet = toreador (tequila, lime, apricot brandy) or Tommy’s margarita (tequila, lime, agave)

See more : Cocktail of the week: Koko kwai from Ka Pao | cocktails

Change Strong = Pegu Club (gin, lime, orange liqueur, bitters) or Cosmopolitan (vodka, lime, orange liqueur, cranberry juice)

Switch up the sour = a margarita made with lemon is delicious too!

Most cocktails have variations that simply swap one ingredient for another on the same side of the triangle—the margarita, for example, has a few side effects.

Most cocktails have variations that simply swap one ingredient for another on the same side of the triangle—the margarita, for example, has a few side effects.

You can do this on purpose to experiment with new versions of some of your favorites, but you can also do it on the fly if you’re missing a specific ingredient. Think about what could serve the same role in the triangle of taste. This could be something else from your bar or something from your kitchen – ripe berries or honey make great sweeteners, and vinegars can be used to add acid. It also means you don’t have to worry about having a bottle of every spirit in your bar, which can get very expensive very quickly.

How to modify drinks using the flavor triangle

Melbourne waitress Cara Devine. Photography: Gareth Sobey

Melbourne waitress Cara Devine. Photography: Gareth Sobey

So what do you do if disaster strikes, when you taste your drink and it’s “too much” of something? The obvious answer is to add more of any ingredient to counteract what’s unbalanced: more sweetener if it’s too sour or bitter, or vice versa. That’s absolutely your first port of call – an extra scoop of something on the bar often works wonders – but consider your building blocks of flavor as well. Adding a large amount of a single ingredient will end up dominating everything else. Instead, think about introducing another complementary element on the same side of the triangle of taste.

Very strong? Often a further dilution is all that is needed; try making it by mixing with ice rather than just adding water, as the chill factor is also important in making a smooth cocktail. That said, a lack of sweetness can also make a drink taste too strong or drunk: sugar rounds off any rough edges, especially if your base is spicy like rye whiskey or some scotch.

Too sweet? Try to combine the forces of sour and bitter. If your main balancing ingredient is citrus, but you don’t want the cocktail to end up too lemony, try a dash or two of cocktail bitters to dry it down. Soda water, tonic water, or sparkling wine also work well: lengthening a drink decreases the perception of sweetness, with the added bonus of introducing extra bitterness (tonic) or acid (wine).

Too bitter? What starts out as woody intrigue can easily turn into unpleasant astringency. First, make sure your “strong” base can handle your bitter ingredient; Rounder spirits like rum and bourbon, for example, will hold up better to intense bitter notes than something more neutral like vodka. A little sugar also goes a long way; a bar spoon amount will often be enough to line up a stubborn bitter ingredient without making the cocktail sweet. While not part of the flavor triangle per se, salt can help too: A drop of saline removes any harshness.

It is good to keep in mind that bitterness is something that people perceive differently. Many bitter drinks are also quite strong, so lengthening them can make them more accessible—for example, try Campari in a fizzy Americano instead of a negroni.

Too sour? Look on the sweet side. But syrups and liqueurs can easily overpower with their pronounced flavors. Sometimes simple is best – just use sugar syrup! Fruit juices can add a mild sweetness that is less viscous; For example, if the recipe calls for elderflower liqueur and you need more sweetness but don’t want it to end up too floral, apple juice is a good choice.

Old fashioned – recipe

The old fashioned is really the closest drink to the original definition of a cocktail (liqueur, sugar, bitters, and water), but it obviously had to go out of style in order to go out of style. It originally had the less critical name of a whiskey cocktail and was called that for several decades.

So what happened to make this simple yet delicious drink go out of style? Well, by the 1870s, bartenders had begun to have more access to liqueurs and other flavor modifiers. They got a little excited and started producing “enhanced” whiskey cocktails. As with any attempt at modernization, there were those who resisted. Plenty of people have laid claim to the old-fashioned name, most notably the Pendennis Club in Louisville, where the story goes that a grumpy local bourbon distiller asked for an “old-fashioned” cocktail, so the bartender took it back to basics. (with the addition of ice so clearly the grumpy bourbon distiller was not against all modern conveniences).

See more : How to make the perfect cheese empanadas – recipe | Food

The old fashioned: ‘the closest drink to the original definition of a cocktail’. Photography: Gareth Sobey

The old fashioned: ‘the closest drink to the original definition of a cocktail’. Photography: Gareth Sobey

You may have seen bartenders drizzle a sugar cube with bitters and stir it in the bottom of the glass. You absolutely can do it this way; I just find that you have more control (and no undissolved sugar crystals) when using sugar syrup.

Flavor triangle: whiskey, sugar syrup, bitters

Ingredients

60ml whisk(e)y

7.5 ml sugar syrup

2 dashes of Angostura bitters

2 dashes of orange bitters

Ice: big block

Garnish: twist of orange zest

Equipment

Glassware: rocks glass

Extent

mixing glass

julep strainer

bar spoon

Place all ingredients in a mixing glass and stir to desired dilution (I like to dilute slightly and let it develop over ice in the glass). Fold your orange twist over the top to expel the oils, then use as a garnish.

Shoemaker from Jerez – recipe

Like the mint julep, the rise in popularity of the cobbler was closely related to the spread of commercial ice. The wine base makes this drink a more sensible choice on a hot afternoon than whiskey.

Gustatory triangle: Sherry Amontillado, Sherry PX Orange, Lemon and Bitter

Ingredients

2 orange segments

2 lemon wedges

60 ml amontillado sherry

15 ml Pedro Ximenez sherry

1 pinch of bitters (optional)

Crushed ice

Garnish: mint sprig, fresh berries, and white granulated sugar

Equipment

Glassware: goblet or rock crystal

Extent

shaker tin

Hawthorne Strainer

bar spoon

Straw

Squeeze the orange and lemon into the shaker tin. Add the sherries and bitters, fill with ice and shake vigorously! Strain over crushed ice, or an easy solution is to “shake and throw” – don’t strain at all but pour the entire contents of your shaker into the glass if you don’t have crushed ice. Broken ice gives the effect you are looking for. Use your bar spoon to suspend the wedges through the drink. Garnish with mint and fresh fruit, sprinkle with sugar and – should be served with a straw.

-

This is an edited excerpt from Cara Devine’s Strong, Sweet and Bitter, photography by Gareth Sobey, available now through Hardie Grant ($36.99)

Source: https://cupstograms.net

Category: Uncategorized