How to make the perfect lentil soup – recipe | Soup

Many cultures have lentil soup as part of their culinary repertoire: the comforting way in which it thickens and enriches a broth has endeared it to cooks from Colombo to Casablanca, and beyond. The local version below has warmed my stomach and heart, on many a wet walk or chilly bike ride, often bolstered by a scone or buttered bannock – the soup is still taken seriously in Scotland, where it rarely finds a coffee that doesn’t. I offer at least one example. The lentil variety is an old favorite that, as Tom Morton explains in Shetland: Cooking on the Edge of the World (the book he wrote with his son James, as well as the island where I enjoyed a great bowl last fall). “Keep it simple.” But what is the best way to do it?

- How to rescue a homemade cocktail: ‘Don’t worry about having a bottle of each liquor’ | australian food and drink

- Britney Spears Reflects on Madonna Kiss — and Her Mentorship in ‘The Woman in Me’

- Cooking dinner means facing danger, but it’s a risk I’m willing to take | Food

- How to make the perfect creamed corn – recipe | Food

- How to eat: a BLT sandwich | sandwiches

the lentils

Lentils, and legumes in general, have been eaten in the UK for centuries, but were often discarded as animal feed, fit only for the poor. However, the poor, or at least the thrifty, did them justice. In that spirit, while I try recipes that specify red lentils, as well as some that mention the green or brown variety, and some that just call for “lentils,” I advise using whatever you have on hand. Correspondents tell me that the red variety is more common in traditional Scottish cooking and actually breaks down better to thicken the stock, but possibly the brown variety has a deeper and more interesting flavour. However, Morton is clear: “Whatever meat or broth base you use, the key is red lentils, not soaked, but washed. For Shetland soup, they should be cooked until almost dissolved.”

You are watching: How to make the perfect lentil soup – recipe | Soup

The vegetables

They all use onions as a base, and Lindsey Bareham also adds garlic and leeks, which, while they certainly won’t spoil the soup, do give it a more continental character in the case of the garlic, and a slightly slimy element in the case of the leek. If you want to use a leek, I suggest adding it a bit later in the process, so it cooks down but doesn’t completely break down.

Potatoes are featured in Bareham’s A Celebration of Soup, Katie Stewart’s Cookbook and Catherine Brown’s Classic Scots Cookery. However, Morton argues against his presence and I tend to agree with him; the lentils are starchy enough on their own, though if you want to bulk up the soup, I’d advise dicing the potatoes, rather than the thinly sliced Browns, which prove rather unwieldy to eat with a spoon tureen.

Where Morton and I differ, however, is on the subject of neeps, or Swedes, as I would call them in London. He won’t be hearing about them in this context, but I love their sweet and sour flavor in Brown’s and SWRI’s recipes, and I think it also pairs really well with the sweetness of the more popular carrots. I’m not a big fan of Bareham and Elisabeth Ayrton’s celery, preferring to stick to the sweeter, starchier root vegetables, but, as with many of those old-fashioned recipes that were designed with economy in mind, I encourage you to make use of the what do you have at home This dish is a very good opportunity to get rid of the vegetables that languish in the bottom of the fridge.

The action

Catherine Brown’s lentil soup has “an intriguing sweet and sour taste.” Felicity Cloake miniatures.

Catherine Brown’s lentil soup has “an intriguing sweet and sour taste.” Felicity Cloake miniatures.

Stewart uses chicken broth, but everyone else calls for ham broth or a ham bone and water, making it the ideal final resting place for a Christmas ham bone you might have taking up freezer space, or a Clever way to stretch an already value-for-money knuckle of ham even further. A joint can give you plenty of meat and broth for less than the price of a small packet of shredded ham, especially if you have a pressure cooker or the like. I quite like a smoky edge with the lentils, but whether you choose smoked or unsmoked, cook them submerged in water until just tender, then use the broth in the recipe below.

Ham stock is not easy to buy, but if you don’t want to mess around with a whole hock, many shopkeepers and butchers should be willing to sell you, or even give you, ham bones. Alternatively, go along with the idea by starting the soup with fatty bacon, as Ayrton suggests in his book The Cookery of England, and use chicken stock instead. (If you eat chicken but not pork, you can add an extra tablespoon of poultry or beef fat to the pan when frying the vegetables.)

See more : Sí se puede: how to make chicken in a beer can – recipe | Chicken

I can’t find any recipe for making this soup with water, but it would certainly have been often in lean times. However, plant-based would do better with a good vegetable stock, plus a generous splash of oil for richness.

Aromatics and flavorings

The Scottish Women’s Rural Institute pushes the boat forward by adding curry powder to their lentil soup.

The Scottish Women’s Rural Institute pushes the boat forward by adding curry powder to their lentil soup.

Our old friend bay leaf makes an appearance in most recipes, but otherwise aromas tend to be quite restrained, with Brown and Ayrton adding parsley, and also thyme and celery or leek leaves. Bareham adds nails, and Ayrton and the SWRI mallet; in fact, rural women are the most daring of the lot, because they finish their soup with curry powder. I like the spicy sweetness of the mace (nutmeg would be a good substitute), but, equally, you can be content with bay leaf and a few turns of the pepper mill.

Brown’s recipe has an intriguing sweet and sour flavor from the tomato puree, lemon juice and molasses he includes along with a dash of red wine, while Bareham also calls for lemon juice, albeit with white wine where appropriate, while Ayrton adds a bit of sugar. Although I would prefer to use vegetables as sweeteners, a hint of acidity isn’t unpleasant on the finish, especially if you serve it in the spring, rather than the dead of winter.

thickeners

Puree a little, leave the rest chunky: Lindsey Bareham’s Lentil Soup.

Puree a little, leave the rest chunky: Lindsey Bareham’s Lentil Soup.

Ayrton makes his white lentil soup with milk and tops it with double cream, so it’s extremely rich, nutty and delicious too, but it’s better served in small portions than steaming vats. Both she and SWRI use flour (“lentil, rice or coarse” as rural women say), but I like Bareham’s idea of pureeing a bit of the soup and then stirring it to thicken better. the broth. If you value smoothness, you can put it all in a blender or even, following the SWRI recipe, pass it through a strainer if you can find one, but I like the vegetable bits in the Brown and Bareham versions, so I’m not going to annoy

To end

In the recipes I try, sips of bread (as croutons were once called), chopped parsley, and even olive oil are suggested, but there’s nothing better than a bannock.

perfect lentil soup

Homework 15 minutes

Cook 1 hour

It serves 4

2 tablespoons of oilor dripping

2 liters of ham brotho 1 ham bone o 150 g of chopped streaky bacon and 2 liters of chicken broth (or water)

2 onionspeeled and finely chopped

2 large carrotstrimmed and diced small

½ neep/half Swedishpeeled and cut into small dice

250g lentils (I like red), washed

½ teaspoon ground mace

salt and black pepper

1 bay leaf

See more : Ravneet Gill Recipe for Chilled Rice Pudding with Apples | Food

Put the oil in a large saucepan over medium heat, then fry the bacon, if using, until lightly browned and the fat begins to melt.

Add the onions, carrots and neep, and fry, stirring regularly, until the onion is golden brown and the other vegetables begin to soften.

Stir the lentils until they are well coated in fat, then add the mace, a pinch of salt, a good grind of pepper and the bay leaf.

Now add the ham broth, or the ham bone and two liters of chicken broth or water, depending on what you are using.

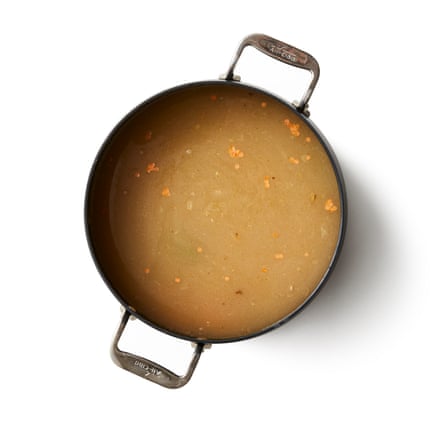

Bring to a simmer, then lower the heat, partially cover the pan, and let cook for about 45 minutes, until the vegetables are soft and the lentils have mostly broken down.

Remove and discard the bay leaf and ham bone, if necessary. Scoop out about a third of the soup, blend until smooth, then return to the pot. Adjust the seasoning to taste and enjoy.

Source: https://cupstograms.net

Category: Uncategorized